Tom Pacheco can rattle off the names of prominent coastal ranching families in one breath: the Moores, the Steeles, the Cunhas, the Gomeses, his own. Five generations later, most of these families have sold their ranches rather than tangle with messy inheritances- in his case, his father was one of nine.

“Most of my generation who grew up around ranches is still doing work around ranches,” he said, “but their families had to sell their places.”

So today, like most ranchers on the coast, Pacheco ![]() leases land from private and public landowners, including the trust and the district. He even ranches some of the land his family worked in the 1920s, now open space.

leases land from private and public landowners, including the trust and the district. He even ranches some of the land his family worked in the 1920s, now open space.

Pacheco is one of three ranchers who practice conservation grazing on district lands. He agrees with conservationists who see cows as management tools for open space ranchland. “You can’t let a grazed property go back to nature. When they do, the brush comes in, the poison oak comes in,” he said. “Pretty soon the fields are full of brush, and it chokes out wildlife.”

Pacheco has always leased land for his cattle. “How are you going to buy a 500-acre ranch around here?” Pacheco said. “Very few people around here could do that. You have to be in some other game to afford that.”

He’s also one of the few full-time cattle ranchers on the coast, but he’s held down a variety of jobs. “Most people do it part-time,” he said. “You have another job- construction, usually. I did many other things when I was first involved in cattle.”

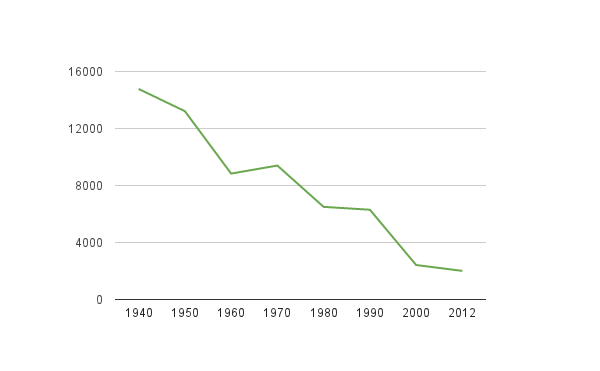

Average head of cattle in San Mateo County, 1940-2012.

Pacheco is optimistic about the county’s ranching future, saying he knows young people who are eager to jump into the industry, even if only part-time. He also believes conservation grazing will keep some ranching alive for many more years.

“I think ranching will continue here because open space groups have discovered that the best way to maintain these places is to keep someone on the land,” he said.

Bob Meehan of Driscoll Ranch agrees, and hopes open space groups will continue to call on local ranchers for the job. “You can’t get some consultant who has read about this work in a book,” he said. “Unless you live on the land and you know it, you’re not going to get it. There will be a slow learning curve for anyone who isn’t familiar with the land.”

Erik and Doniga Markegard’s ![]() Toto Ranch, the open space property where they live and work, sits on sweeping hillsides overlooking Half Moon Bay. Erik is a sixth-generation rancher whose family immigrated from the Dakotas. His family managed land that would become Driscoll Ranch, as well as the ranch of musician Neil Young. Doniga is a naturalist and wildlife tracker who worked on conservation research before settling in California.

Toto Ranch, the open space property where they live and work, sits on sweeping hillsides overlooking Half Moon Bay. Erik is a sixth-generation rancher whose family immigrated from the Dakotas. His family managed land that would become Driscoll Ranch, as well as the ranch of musician Neil Young. Doniga is a naturalist and wildlife tracker who worked on conservation research before settling in California.

Erik grew up on a coast where ranching was viable. He started putting together his cattle herd while in high school. He first ranched cattle at the Toto Ranch in 1987, when it was still privately owned.

Today, the Markegards raise grass-fed beef, which means their cattle graze pastures as opposed to being fed grain or other feed. They also use their cows as land management tools, and Doniga said the results can be impressive.

“It’s like night and day,” she said. “You can have fields that are completely covered with Italian thistle and coyote brush, and with intentional grazing, giving the land time to rest and recover, you can see a huge diversity of plants and animals come back.”

Both Erik and Doniga have made peace with the fact that they likely will never own their own ranch in the county. But they do intend to keep ranching in their family. Leasing land from open space groups on a long-term basis has been a good fit. “We’ll never afford our own land, so the next best is land that’s never going to change,” Doniga said. “With a long-term lease, our kids can use this land.”

Leasing private land is trickier. “There’s no security with a private owner because of the outrageous value of private land,” Erik said. “I can’t blame owners for not wanting to lease their land because they could get four times the value selling it.”

In all, the Markegards have learned to adapt. “We’re not going to stop progression and change,” Erik said, “so we go with it.”

“We want to be ahead of the curve,” Doniga said. They have an active relationship with the distrct, and say they are completely aligned with their biologists.

“Whether private, public, or non-profit, stewards should live on the land and be connected to every season,” Doniga said.

Rudy Driscoll, Jr hopes that more landlords- both public and private- recognize that ranchers have value to bring to land management. “The old time ranchers here, they have been doing these practices for years but have not been given credit.”

Doniga agrees. “Ranchers have always been interested in the management of grasslands. You didn’t call it that, it’s just what you did.”

Credits:

Top image: Visitors look through photo albums of rodeos past at Driscoll Ranch.

Data: Cattle data courtesy of the San Mateo County Agricultural Commissioner.