Open space groups have had a long relationship with rural San Mateo County.

The most prominent, the public Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District, is funded primarily through a portion of annual property taxes collected from residents in San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz counties.

In 1972, Santa Clara County voters approved Measure R, a ballot initiative that created the precursor to the modern district. The measure was a work of poetry. “Open space is our green backdrop of hills,” an excerpt reads. “It is rolling grasslands – cool forests in the Coast Range – orchards and vineyards in the sun.”

Today, the district oversees almost 62,000 acres within 26 open space preserves. The goal is to keep the preserves mostly untouched, with trails and parking often the only additions, and open to the public, as the vast majority are.

Open space and preserved land in the Bay Area.

The second, less high-profile group, is the Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST), a nonprofit founded in 1977. Where the district was a government entity, at times slow moving and bureaucratic, POST was intended to be quick and effective.

Funded by private donors, the trust can reach out to landowners who are considering selling and buy land faster than the district. It can also arrange conservation easements for landowners who want to maintain ownership but don’t want to see their land developed.

Later on, POST can partner with the district, the National Park Service or California’s state parks to add purchased land to existing preserves or parks, or keep the land on its own ledger.

In the late 1990s, public opinion was shifting among San Mateo County residents, as many more prioritized preservation of the Pacific coast. A decade later the district’s board voted to add coastal lands to its territory. The so-called Coastside Protection Plan expanded their borders from Pacifica to the Santa Cruz County line.

220

In addition to preserving land, the district wanted to help preserve the area’s rural character and agricultural economy.

One way of doing this was leasing open space back to farmers, which POST had begun in the late 1990s. Another way was leasing the land back to ranchers, but to do that district managers needed to adopt new, cow-friendly policies.

Kirk Lenington manages grazing policy for the district. He remembers a time when cows were frowned upon in open space preserves. The science and research behind conservation has changed since then, he said, as researchers look to history and see a new role for cattle — a method called conservation grazing.

“California grasslands evolved with historic grazing pressure” from animals like antelope and deer, he said, “and grass evolved to be able to tolerate grazing.”

When Europeans arrived ![]() with cattle, they also tracked in seeds from non-native grasses that overwhelmed the native species.

with cattle, they also tracked in seeds from non-native grasses that overwhelmed the native species.

Traditional methods like controlled burns and mowing aren’t always feasible in the large acreage of open space preserves. Cattle became a good option. “Cattle grazing works really well, but you have to manage it,” Lenington said.

Controlling the number of cattle and the length of time they spend on a given piece of property are key. A well-managed herd can chomp through both non-native grasses and dead grass that would otherwise become fuel for wildland fires.

“It’s good for us on a number of levels,” Lenington said. “In addition to being a good land management tool, our tenants are our eyes and ears on the land.”

The district opened its first preserve to grazing in 2007, and now allows the practice on roughly 7,700 acres, with plans to reach 10,800 acres by next year. The trust also leases some of its property for grazing.

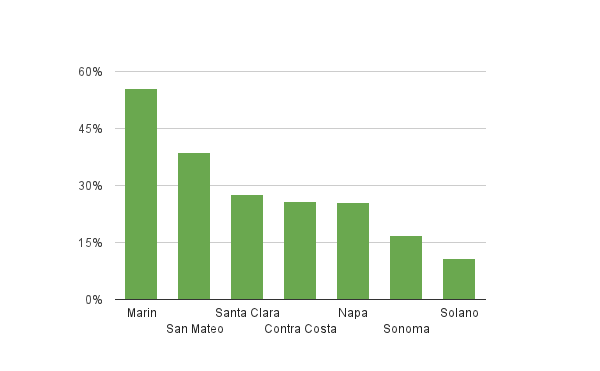

Percentage of permanently protected land in the Bay Area in 2012, by county.

Thanks to geography and low population density, open space in San Mateo County is still more likely to be found clustered along the Santa Cruz Mountains and westward.

Today, when Chris Pearson ![]() , a third-generation farmer in La Honda, gets off his tractor and looks around, he sees mostly preserved land. “Open space land is just across the road from my property,” he said. “I’m almost entirely surrounded by public land.”

, a third-generation farmer in La Honda, gets off his tractor and looks around, he sees mostly preserved land. “Open space land is just across the road from my property,” he said. “I’m almost entirely surrounded by public land.”

The grazing program has plenty of company in Bay Area counties with large tracts of public land. Marin County, Santa Clara County and areas in the East Bay all invite grazing.

Denise Defreese oversees grazing operations on public land for the East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD). The Park District has grazed their land since the early 1960s. She estimated that 37 ranchers lease and graze roughly 80,000 of their 112,000 acres of parkland.

“I can’t see how you can manage grasslands without grazing animals,” she said. “People thought if they removed grazing, they would get pristine meadows. But grass has evolved to be eaten, so if there is no eating, you get something else.”

Credits:

Top image: A grazing herd on district land.

Images: Map courtesy of Geographicus/public domain.

Data: Map data courtesy of the Greenbelt Alliance. Expansion statistic courtesy of MROSD. Graph data courtesy of the Greenbelt Alliance.